Years ago, when I played an active role in running my veterinary practice, something odd tried to get my attention on multiple occasions. I don’t hear voices or see ghosts, so I don’t really know how to explain it. Perhaps it was an awareness or something my subconscious mind wanted to reveal. It made no sense to take it any further. Besides, I didn’t find Freud’s explanation of the self to be all that useful.

Since I have started to write this blog, I’m wondering if it was some sort of premonition that awaited a future me. I do remember my response at the time – it was a flat no. No way, I don’t have the time to write a book. Besides, dredging up the many emotional battles I have faced down seemed too ugly. My psyche needed time to recover, not remember.

That persistent prompting also delivered an odd title for the book, The Woman Vet. My “whys” about why I would not want to write a book detailing my life experiences have mellowed with age and wisdom. A five-year sabbatical has helped to soften painful memories just enough that I can finally talk about them.

With hopes that my struggles and insights, collectively spanning decades, will feel like a tell-all conversation with your best friend, here’s the chapter I finished this week. With a box of Kleenex next to my laptop…

Chapter 8

Lucy

I had secretly wanted a Scottish terrier, but it violated my principle to seek out breeders. The rescue mindset prevailed, and I made no secrets about it. It became an unspoken rule to my staff – adopt. So, when a client had bred her Scottish, and I knew the puppies were in an exam room waiting for me to bounce in, I tried to hide my enthusiasm. It didn’t work and before I knew it, I was offered a puppy. Six weeks later I brought Lucy home. We would enjoy seven wonderful years together before trouble started. Something about Lucy was not right. First, I noticed her appetite was off. Ho hum appetites often offer us the earliest clue. It’s the one commonality that many illnesses share. So, watch out for any changes in appetite. It’s when you really need to start paying more attention.

Good doctors work in earnest like experienced puzzle solvers. Moving information around until everything fits. After talking with clients and asking lots of questions, we analyze the patient’s history for relevant information. Next, our hands, eyes, and ears go to work. We make pertinent observations and record data. Sometimes, after just putting these two pieces together, we can look like a genius – puzzle solved. If not, we go back to gather more information. Next, we order routine lab work, like blood tests (CBC and chemistry panel) and a urinalysis. Adding another two pieces of data hoping to solve the puzzle. Looking at Lucy’s lab reports only helped to rule out things like kidney or liver disease and blood cell abnormalities. Her symptoms remained an unsolved puzzle. Next came radiographs of her chest and abdomen. First real clue discovered – a suspicious shadow on her chest radiograph.

After my initial work up, I consulted a veterinary radiologist. We discussed my dog like a typical patient. But there was nothing typical about how I was feeling. Dr K confirmed the abnormal density seen on the chest films. Without any more discussion, a biopsy of the suspect mass was recommended. I was unprepared for that news. He just confessed that a tumor was first on his list of possibilities. Shit! I was rooting for an infection that I could kill with a silver bullet. That I understood ‘doctor talk’ gave me an advantage as the owner of the patient. But it didn’t mean that I would worry any less.

I held back the tears when I called Dr W – a talented surgeon whom I had worked with during my pre-vet years. I felt lucky that we had stayed friends. Opening the chest cavity to expose lung tissue required major surgery with its associated risks – putting me in the hot seat. As pet owners, we are called upon to make decisions for a life other than our own. Our pets are never consulted. They don’t make decisions. We can’t ask them. Which means they can’t screw up like humans. Oh, the glory of being non-human.

To this day, I believe the surgeon was acting on what he believed to be the best call. He removed the mass and sectioned off a part to peer at it under the microscope. He reported the likelihood of it being a malignant tumor. I was devastated and pressed him hard. Are you sure? He would not commit. He was not a pathologist. Then, he threw another curve ball. “You know, if this is cancer and we wake up Lucy, she will be in a lot of pain.” And without saying it, he did say it. If we wake Lucy up from anesthesia, she will die a painful death in the coming weeks or months. Don’t let her suffer.

I took a veterinary oath to prevent and provide the relief of animal suffering.

“Being admitted to the profession of veterinary medicine, I solemnly swear to use my scientific knowledge and skills for the benefit of society through the protection of animal health and welfare, and the prevention and relief of animal suffering.”

In an agonizing moment, I let Lucy go. That morning on the drive to the hospital, I had reassured Lucy that everything would be all right. I don’t feel guilty about saying those words because I was really talking to myself, as we know that’s what humans do. But I did something else that was not predictable. I retrieved the entire mass and sent it out to a pathologist for examination. Of course, it would not matter for the patient, but it was the closure I personally needed. The report would confirm that I made the right choice. Except that it didn’t.

Three days later I got the pathology report back. The diagnosis hit me hard. Neither the radiologist nor the surgeon had considered the possibility. Here’s the lesson I would never forget. It’s possible for the experts that advise us to get it wrong. I became haunted by this question. Had I abdicated my own responsibility by handing over the reins to more experienced doctors? The answer was a harsh, “I guess so.” In vet school, we are taught how to determine a differential diagnosis for each patient. That means, after doing a thorough patient workup, it’s time to write down a list of every possible disease that could be matched to the patient’s symptoms. Just keep looking (more tests, additional physical exams, get another doctor’s opinion) until you find the last piece that solves the puzzle.

We test our differential diagnosis list on each suspect until the real criminal is found. Infectious causes, like an abscess, had been on my hopeful mind the very first time I looked at Lucy’s X-ray. Why? Because infections have treatment plans unlike cancer. The shocking pathology report identified an infection of fungal origin. The pathologist labeled the final puzzle piece. Not me or my trusted colleagues. In the mist of my grief, anger was not far behind.

You won’t find this cocktail in a bar. It’s a mixture of grief and anger topped off with a heavy amount of guilt. It was toxic, and I drank it every day for years. Lucy’s fungal disease could have been diagnosed with a simple blood test. But I, and my esteemed colleagues, had failed to make a complete text book differential diagnosis list. So, the test was never ordered.

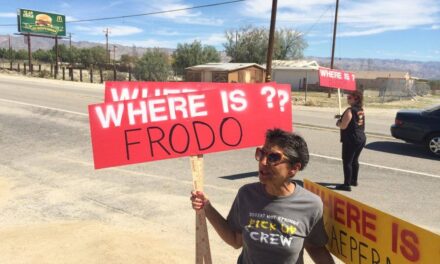

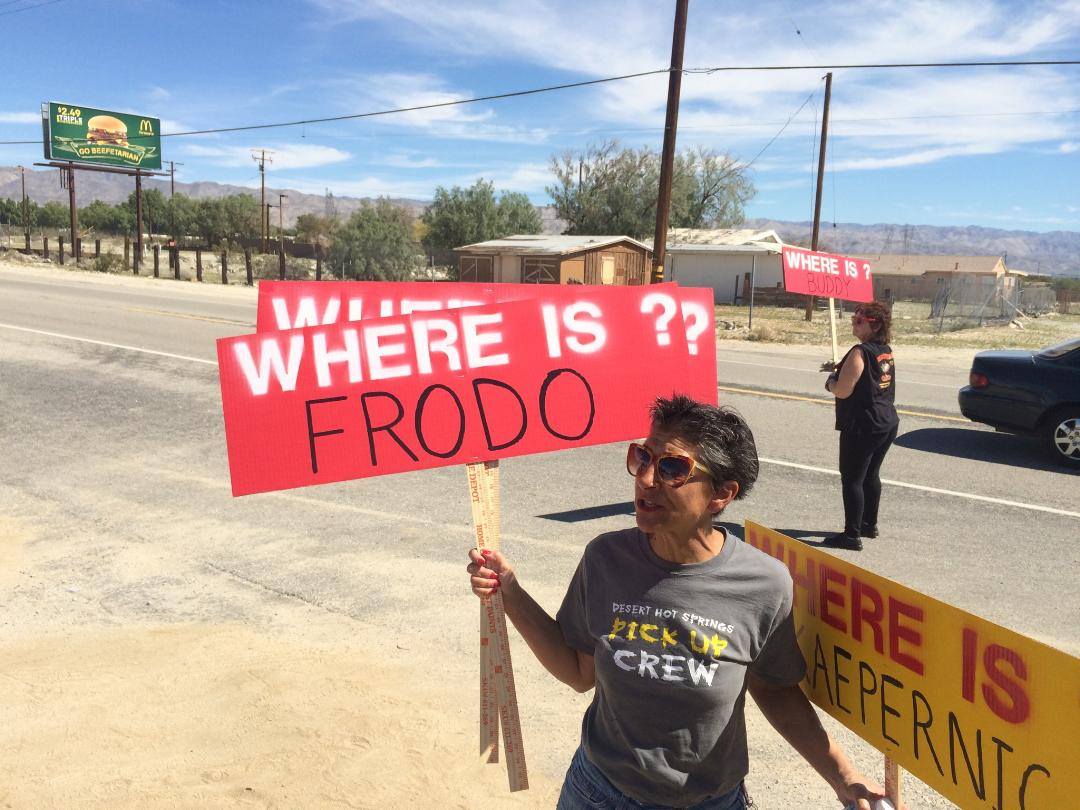

One thing missing from Lucy’s patient history were our frequent visits to Palm Springs for weekend getaways. Palm Springs makes up one of nine cities located in the Coachella Valley. Our second home condo was on a map of Southern California deserts – southeast from the San Bernardino Mountains to the northern shore of the Salton Sea. In general, residents of Southern California (more often the Central Valley) could encounter this soil organism just by breathing. Arid desert windstorms and construction sites are dust blowing machines. When the fungus gets a lift, airborne spores can be inhaled. This was to be Lucy’s fate.

Depending on geography, wherever you live or just visit, its likely there are inherent risk factors lurking. Like mosquitos and malaria in parts of Asia. Or heartworms in northern California. Keep in mind the places you’ve lived and visited. It’s a relevant part of your, and your pet’s history. Respiratory symptoms (such as persistent cough or difficulty breathing accompanied by fatigue and possible fever) that do not respond to conventional therapies should raise an eyebrow for Coccidioides immitis – known as Valley Fever in people.

For people and pets living in or visiting arid to semi-arid areas of the southwestern United States, this fungus should be on every doctors differential list for respiratory symptoms that persist or fail treatments for suspected viral and bacterial infections. I was only partially right about what might be causing Lucy’s symptoms. She had an infection. There are four classes of infectious agents: bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. I had been stuck on only one – bacterial. The price of missing the correct diagnosis and losing a patient is every doctor’s worst nightmare. By the end of that same year, my marriage had ended. I lost both my beloved Lucy and my best friend just shy of 12 months. It was the year from hell. I was a walking zombie.

Unlike the mind games played in vet school, this time I was tossed into a new bucket of suffering. Dealing with the crisis of wounded soul and self-doubt. There was no date when l could expect to graduate from this double dose of grief and move on with life. In my zombie-like state, Mom helped me pack up and sell my house. Then strangely, I went to live with one of my sisters. Something my rational mind would never do. At least I had landed in a safe place and didn’t do anything rash or stupid. In the dog-less time zone that followed, my divorce was finalized. There would be a lack of laughter and fur in the new house. I was lost in misery. It would take another client with puppies to change that one year later.